Engineer Recalls Work On Manhattan Project

/By Andrew Wroblewski

awroblewski@longislandergroup.com

It was the early 1940s, in the midst of World War II, and both the United States and Nazi Germany were barreling down a road headed toward creating the deadliest weapon ever known to man.

Melville’s Meyer Steinberg, now 91, was one of the people who helped create it as part of the top secret Manhattan Project. The project produced the atomic bomb and ultimately sided the war in favor of the Allies after the U.S. unleashed two bombs, “Little Boy” and “Fat Man,” respectively on Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945 on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. While the bombings killed more than 246,000, they also ended World War II and effectively saved “a tremendous amount of lives,” he said.

“We knew that fission was actually discovered in Europe, so we were in a race with Nazi Germany. We were very much concerned that, if Hitler got it first, it would have been devastating,” he said.

Steinberg’s commitment to the Manhattan Project started a little more than a year prior to the bombings.

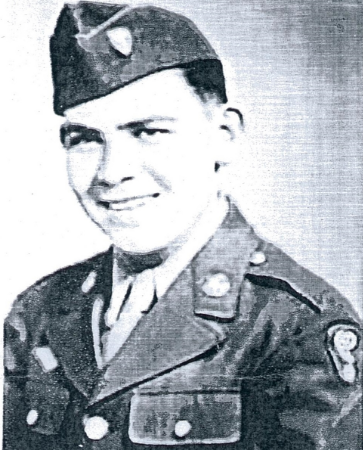

Hailing from Astoria, Queens, Steinberg joined the Army Reserve after graduating with a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from Cooper Union in Manhattan in June 1944.

Just 19 years old, Steinberg began work in New Jersey inspecting nickel-plated pipe for the Kellex Corp., a division of the M.W. Kellogg Co. that the company specifically created for the Manhattan Project. After inspection, the pipe was sent to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to be used in assembling the K-25 uranium enrichment facility. Steinberg soon followed the pipe and was assigned to perform fluid-flow calculation in Oak Ridge to help build K-25, where the fissionable Uranium-235 was isolated to create “Little Boy.”

In early 1945, the engineer moved to New Mexico and continued working on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos Laboratory. Steinberg worked to isolate Plutonium-239, which is also fissionable and the key ingredient to “Fat Man.”

“We had a change of clothes every day, had to wear masks and worked through glove boxes,” in order to stay safe, he explained. “We made enough material there to make the first bomb.”

The first test of a nuclear weapon was carried out in Alma Gordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, just six says after Steinberg’s 21st birthday. That test bomb was dubbed “Gadget.”

Now nearly 70 years after the bombs were dropped in Japan, Steinberg believes the act was a necessary evil. The world, he said, needed to see the effects of nuclear warfare.

“It showed how terrible this is and how it should never be used again,” he said.

Steinberg said he’s had several veterans of the war thank him for his involvement in the project. To those men and women, Steinberg effectively saved their lives.

“If they would have had to invade Japan after taking the Marshall Islands and others, there would have been a great slaughter,” Steinberg said.

A member of the U.S. Army’s Special Engineer Detachment, Steinberg was discharged in June 1946. Three years later, he earned a master’s degree in chemical engineering from the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn.

In 1950, he married Ruth Elias, and six years later the couple moved to South Huntington.

In 1953, Steinberg became a certified chemical engineer and, after a stint with Guggenheim Brothers, he joined Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1957. He worked for the laboratory for the next 40 years, becoming a senior chemical engineer and head of the process sciences division in the laboratory’s department of applied science.

Steinberg’s research eventually brought him to indulge in carbon dioxide control technologies, as applied to the global greenhouse problem caused by the burning of fossil fuels.

“I started back in the ‘70s, when very few people were looking at this,” said Steinberg, who co-authored a book detailing methods and potential methods of reducing carbon dioxide emissions. “It was a natural development in my career since I was working on energy and environment.

With more than 500 publications and 38 patents to his name, Steinberg retired in 1997. Ruth died in 2009. The couple had two sons, Jay and David. Steinberg remarried in 2012 and now lives in Melville with his wife, Phyllis Simon.

Steinberg still carries a little piece of the world’s greatest secret along with him each and every day – one that he believes is helping to keep him healthy.

“Plutonium has a half-life of 23,000 years, and it’s like calcium in that it gets in the bones and stays in there,” he said.

Even though it’s a small amount, Steinberg said his body has been measured to contain more than 10,000 times the average amount of plutonium.

“There are two theories of radiation. One states that any type of radiation is no good for you. Then, there’s another that states… a small amount could actually be beneficial to you,” he explained, stating the second theory is known as hormesis. “Well, I’m 91 now and I’m a believer.”